Misguided killer T cells may be the missing link in sustained tissue damage in the brains and spines of people with multiple sclerosis, findings from the University of Washington reveal. Cytoxic T cells, also known as CD8+ T cells, are white blood cells that normally are in the body’s arsenal to fight disease.

Multiple sclerosis is characterized by inflamed lesions that damage the insulation surrounding nerve fibers and destroy the axons, electrical impulse conductors that look like long, branching projections. Affected nerves fail to transmit signals effectively.

Intriguingly, the UW study, published this week in Nature Immunology, also raises the possibility that misdirected killer T cells might at other times act protectively and not add to lesion formation. Instead they might retaliate against the cells that tried to make them mistake the wrappings around nerve endings as dangerous.

UW Immunology chair Joan Goverman studies the cellular mechanisms behind autoimmune disorders of the central nervous system.

Scientists Qingyong Ji and Luca Castelli performed the research with Joan Goverman, UW professor and chair of immunology. Goverman is noted for her work on the cells involved in autoimmune disorders of the central nervous system and on laboratory models of multiple sclerosis.

Multiple sclerosis generally first appears between ages 20 to 40. It is believed to stem from corruption of the body’s normal defense against pathogens, so that it now attacks itself. For reasons not yet known, the immune system, which wards off cancer and infection, is provoked to vandalize the myelin sheath around nerve cells. The myelin sheath resembles the coating on an electrical wire. When it frays, nerve impulses are impaired.

Depending on which nerves are harmed, vision problems, an inability to walk, or other debilitating symptoms may arise. Sometimes the lesions heal partially or temporarily, leading to a see-saw of remissions and flare ups. In other cases, nerve damage is unrelenting.

The myelin sheaths on nerve cell projections are fashioned by support cells called oligodendrocytes. Newborn’s brains contain just a few sections with myelinated nerve cells. An adult’s brains cells are not fully myelinated until age 25 to 30.

For T cells to recognize proteins from a pathogen, a myelin sheath or any source, other cells must break the desired proteins into small pieces, called peptides, and then present the peptides in a specific molecular package to the T cells. Scientists had previously determined which cells present pieces of a myelin protein to a type of T cell involved in the pathology of multiple sclerosis called a CD4+ T cell. Before the current study, no cells had yet been found that present myelin protein to CD8+ T cells.

Scientists strongly suspect that CD8+ T cells, whose job is to kill other cells, play an important role in the myelin-damage of multiple sclerosis. In experimental autoimmune encephalitis, which is an animal model of multiple sclerosis in humans, CD4+T cells have a significant part in the inflammatory response. However, scientists observed that, in acute and chronic multiple sclerosis lesions, CD8+T cells actually outnumber CD4+ T cells and their numbers correlate with the extent of damage to nerve cell projections. Other studies suggest the opposite: that CD8+T cells may tone down the myelin attack.

The differing observations pointed to a conflicting role for CD8 + T cells in exacerbating or ameliorating episodes of multiple sclerosis. Still, how CD8+T cells actually contributed to regulating the autoimmune response in the central nervous system, for better or worse, was poorly understood.

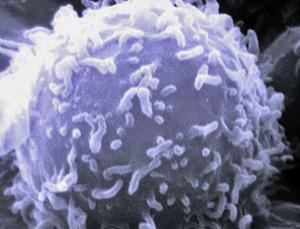

TIP dendritic cells, stained to show their physical features.

Goverman and her team showed for the first time that naive CD8+ T cells were activated and turned into myelin-recognizing cells by special cells called Tip-dendritic cells. These cells are derived from a type of inflammatory white blood cell that accumulates in the brain and the spinal cord during experimental autoimmune encephalitis originally mediated by CD4+ T cells. The membrane folds and protrusions of mature dendritic cells often look like branched tentacles or cupped petals well-suited to probing the surroundings.

The researchers proposed that the Tip dendritic cells can not only engulf myelin debris or dead oligodendrocytes and then present myelin peptides to CD4 + T cells, they also have the unusual ability to load a myelin peptide onto a specific type of molecule that also presents it to CD8+ T cells. In this way, the Tip dendritic cells can spread the immune response from CD4+ T cells to CD8+ T cells. This presentation enables CD8+ T cells to recognize myelin protein segments from oligodendrocytes, the cells that form the myelin sheath. The phenomenon establishes a second-wave of autoimmune reactivity in which the CD8+ T cells respond to the presence of oligodendrocytes by splitting them open and spilling their contents.

“Our findings are consistent,” the researchers said, “with the critical role of dendritic cells in promoting inflammation in autoimmune diseases of the central nervous system.” They mentioned that mature dendritic cells might possibly wait in the blood vessels of normal brain tissue to activate T-cells that have infiltrated the blood/brain barrier.

The oligodendrocytes, under the inflammatory situation of experimental autoimmune encephalitis, also present peptides that elicit an immune response from CD8+T cells. Under healthy conditions, oligodendrocytes wouldn’t do this.

The researchers proposed that myelin-specific CD8+T cells might play a role in the ongoing destruction of nerve-cell endings in “slow burning” multiple sclerosis lesions. A drop in inflammation accompanied by an increased degeneration of axons (electrical impulse-conducting structures) coincides with multiple sclerosis leaving the relapsing-remitting stage of disease and entering a more progressive state.

Medical scientists are studying the roles of a variety of immune cells in multiple sclerosis in the hopes of discovering pathways that could be therapeutic targets to prevent or control the disease, or to find ways to harness the body’s own protective mechanisms. This could lead to highly specific treatments that might avoid the unpleasant or dangerous side effects of generalized immunosuppressants like corticosteroids or methotrexate.

The study was funding by grants AI072737 and AI073748 from the National Institutes of Health. The authors declared no competing financial interests.